Helle Kares was born and raised in Suurupi, in Ranna Village. In the 1700s, her great-grandfather lived not far from here. Her father and uncle worked in Suurupi Lighthouse Rear from 1945. When Helle was a child, she used to spend a lot of time with her aunt and uncle in Suurupi lighthouse. Uncle Elmar Kares was in charge of the Suurupi beacons until 1977. When he retired, he invited Helle to continue the lighthouse keeper’s work. Lighthouses are very dear to Helle and they’re a part of her lifestyle.

Over the centuries, the work of a lighthouse keeper has changed drastically, starting with burning firewood and ending with operating a fully automated flashing lamp. The equipment has become more reliable. The rear beacon of Suurupi was built on the proposal of Peter I and it was completed in 1760. Peter I had begun creating a window to Europe and for this, he needed to create a fairway from Saint Petersburg to Europe. When Helle started work here, there was alternating current here already.

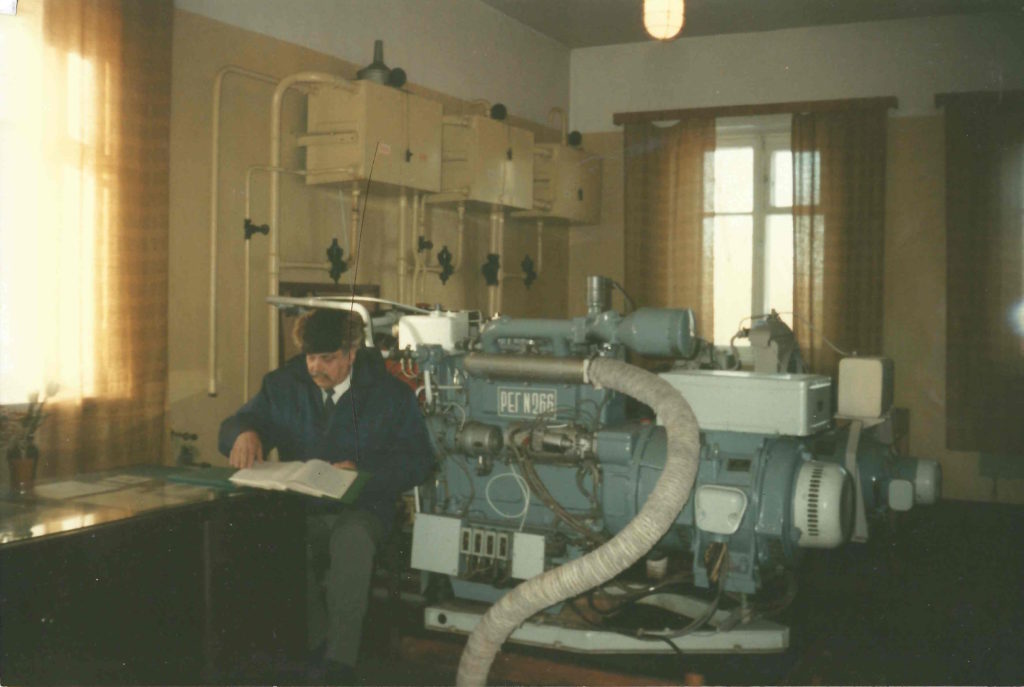

Electricity was brought to Suurupi in the 1960s. But back then, it wasn’t very reliable. Often during stormy and dark nights, batteries and diesel generators had to be used to be able to indicate a safe passage to ships. There were three diesel generators, since lighthouse keeper had to be sure that one of them would work when needed. Those were probably the hardest moments at work, when the diesel generators wouldn’t start.

For a number of years after lighthouse keepers were made redundant in Estonia, Helle used to wake up in the night and check whether the lighthouse was flashing. But the technology kept developing and the towers have now been fully automated since 2004 and everything works. The light is flashing.

The most important part of a lighthouse keeper’s job is to make sure that the beacon works. For this, you need to be responsible and punctual. During your shift, you must make sure that the light turns on when the sun sets and goes off when the sun rises. Right now, the beacon works automatically and the light flashes around the clock.

In addition to the above, a lighthouse keeper had to keep radio contact with other lighthouse keepers, as well as with warships during drills. Radio communications took place four times a day and only with encoded texts, which were of course in Russian. During winter, radio communications took place five times a day, with an additional report on ice conditions. Tasks and duties also included charging batteries, starting diesel generators, weather station operations (ice conditions, fog at sea, nearby fires) and upkeep of premises. I had to manage the work of both Suurupi beacons, as well as the fog siren (foghorn). I operated the foghorn from the lighthouse’s technical building. We made entries in relevant journals (the guard journal and the journal of radio communications) on everything that happened. Lighthouse keepers work was checked by bosses in Tallinn and once a year lighthouse keepers were inspected by admirals from Leningrad and Kaliningrad. In terms of orderliness, we were number one in the Baltics.

The seaway between Suurupi and Tallinn had three sea buoys. Monitoring the buoys was also part of the lighthouse keeper’s job. Namely, the buoys flash a light too, and a good pair of binoculars for checking them was always part of the toolkit in the lighthouse. There used to be no passenger boats between Naissaar and Suurupi. It was prohibited. Only warships or fishing boats moved around here.

Suurupi.Travel

Suurupi.Travel